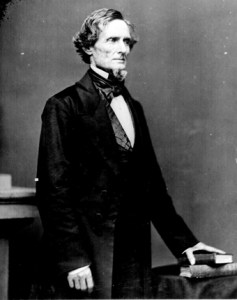

April 10, 1865 – President Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government-in-exile left Danville, Virginia, for Greensboro, North Carolina, upon learning of General-in-Chief Robert E. Lee’s surrender.

When the fall of Richmond was imminent, Davis and his cabinet ministers fled aboard a train bound for Danville, near the Virginia-North Carolina border. Although Danville was just 120 miles away, it took 20 hours to get there.

Citizens of Danville warmly received the Confederate officials when they arrived on the 3rd, and Davis took up residence in the home of Major W.T. Sutherlin. Davis wrote to his wife Varina, who had fled ahead of him and was now in Charlotte. The next day, he issued a proclamation “To the People of the Confederate States of America”:

“The General-in-Chief found it necessary to make such movements of his troops as to uncover the capital. It would be unwise to conceal the moral and material injury to our cause resulting from its occupation by the enemy. It is equally unwise and unworthy of us to allow our energies to falter and our efforts to become relaxed under reverses, however calamitous they may be… It is for us, my countrymen, to show by our bearing under reverses, how wretched has been the self-deception of those who have believed us less able to endure misfortune with fortitude than to encounter danger with courage.

“We have now entered upon a new phase of the struggle. Relieved from the necessity of guarding particular points, our army will be free to move from point to point, to strike the enemy in detail far from his base. Let us but will it, and we are free… Animated by that confidence in your spirit and fortitude which never yet failed me, I announce to you, fellow-countrymen, that it is my purpose to maintain your cause with my whole heart and soul; that I will never consent to abandon to the enemy one foot of the soil of any of the States of the Confederacy… Let us, then, not despond, my countrymen, but, relying on God, meet the foe with fresh defiance and with unconquered and unconquerable hearts.”

Davis hoped that Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia would soon arrive at Danville, but by this time, the Federals were closer than Lee. While Davis and other officials made Danville the temporary Confederate capital, Navy Lieutenant William H. Parker and 50 midshipmen continued south with the government archives, records, and treasury assets.

On the afternoon of the 10th, word arrived in Danville that Lee had surrendered his army. But this did not weaken Davis’s resolve, and he directed that the government relocate ahead of the Federal cavalry. That night, Davis and his cabinet left Danville on a train bound for Greensboro, North Carolina, 45 miles south. He notified General Joseph E. Johnston that Lee had surrendered and requested a meeting when the train arrived. Johnston commanded the last real Confederate force east of the Mississippi River, and Davis wanted to ensure that Johnston did not share Lee’s fate.

Davis’s train arrived at Greensboro on the morning of the 11th to a lukewarm reception. Many citizens in this Piedmont region of North Carolina had long opposed the Confederate war effort, and many others feared that embracing the Confederate government would encourage vengeful Federals to destroy their town. Only Davis and Treasury Secretary George A. Trenholm found lodging in Greensboro; the remaining government officials slept in train cars.

Upon his arrival, Davis received word that the train carrying the Confederate archives and assets had left $39,000 at Greensboro for soldier pay before continuing on to Charlotte. Lieutenant Parker and his midshipmen collected Varina Davis and her children at Charlotte, and then continued southward.

Davis wrote to North Carolina Governor Zebulon Vance: “We must redouble our efforts to meet present disasters. An army holding its position with determination to fight on, and manifest ability to maintain the struggle, will attract all the scattered soldiers and daily and rapidly gather strength.”

Davis also met with General P.G.T. Beauregard, serving under Johnston in this military department, whose headquarters were in boxcars at the railroad depot. Beauregard reported that Johnston had evacuated Smithfield, but Davis disagreed with the general’s assessment that the cause was lost. Davis believed that Johnston could continue the fight, even if it meant retreating west across the Mississippi River.

Davis summoned Johnston to Greensboro to discuss the situation. He wrote: “The important question first to be solved is, at what point shall concentration be made, in view of the present position of the two columns of the enemy, and the routes which they may adopt to engage your forces… Your more intimate knowledge of the data for the solution of the problem deters me from making a specific suggestion on that point.”

Before following the president’s orders, Johnston had been advised by Governor Vance: “(Davis), a man of imperfectly constituted genius… could absolutely blind himself to those things which his prejudices or hopes did not desire to see.”

—–

References

Angle, Paul M., A Pictorial History of the Civil War Years (New York: Doubleday, 1967), p. 219-21; CivilWarDailyGazette.com; Davis, Jefferson, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government: All Volumes (Heraklion Press, Kindle Edition 2013, 1889), Loc 22766-81, 27796-814; Denney, Robert E., The Civil War Years: A Day-by-Day Chronicle (New York: Gramercy Books, 1992 [1998 edition]), p. 554, 556-58; Foote, Shelby, The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 3: Red River to Appomattox (Vintage Civil War Library, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Kindle Edition, 2011), Loc 18705-25, 20295-334; Fredriksen, John C., Civil War Almanac (New York: Checkmark Books, 2007), p. 576-77, 581-83; Long, E.B. with Long, Barbara, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971), p. 665-66, 672-73; McPherson, James M., Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States Book 6, Oxford University Press, Kindle Edition, 1988), p. 847; Ward, Geoffrey C., Burns, Ric, Burns, Ken, The Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), p. 375; White, Howard Ray, Bloodstains, An Epic History of the Politics that Produced and Sustained the American Civil War and the Political Reconstruction that Followed (Southernbooks, Kindle Edition, 2012), Q265

2 comments