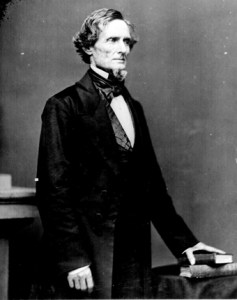

April 22, 1865 – President Jefferson Davis held a cabinet meeting in Charlotte and weighed the Confederacy’s rapidly dwindling options.

Davis and what was left of the Confederate government-in-exile left Greensboro, North Carolina, on the 15th and continued moving south. General Joseph E. Johnston, who had conferred with Davis and his cabinet the previous day, had written to Major General William T. Sherman requesting an armistice to discuss peace. Johnston returned to his headquarters to await Sherman’s answer.

The government officials left Greensboro on horseback, escorted by cavalry, without even informing Johnston. They rode through the night and reached Lexington on the 16th. Meanwhile, Lieutenant William H. Parker led a naval escort that transported the Confederate archives and treasury ahead of Davis’s party; they arrived at Washington, Georgia, on the 17th. That same day, the Davis party reached Salisbury and then continued on before finally stopping to rest at Charlotte on the 18th.

At Charlotte, Davis received word from Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge about the proposed Johnston-Sherman conference. Davis received another message: “President Lincoln was assassinated in the theatre in Washington on the night of April 14. Seward’s house was entered on the same night and he was repeatedly stabbed and is probably mortally wounded.”

Davis handed the telegram to a citizen, who read it to the gathering crowd. Some cheered at the news, but Davis knew better. He said, “Certainly I have no special regard for Mr. Lincoln, but there are a great many men of whose end I would rather hear than his. I fear it will be disastrous to our people, and I regret it deeply.”

Davis also received a letter from Lieutenant General Wade Hampton, commanding the largest remaining Confederate cavalry force. Hampton wrote:

“The military situation is gloomy, I admit, but it is by no means desperate, and endurance and determination will produce a change… Give me a good force of cavalry and I will take them safely across the Mississippi, and if you desire to go in that direction it will give me great pleasure to escort you… I can bring to your support many strong arms and brave hearts–men who will fight to Texas, and who, if forced from that state, will seek refuge in Mexico rather than in the Union.”

While Hampton urged Davis to fight on, General-in-Chief Robert E. Lee offered his assessment of the situation in his final report to the president:

“The apprehensions I expressed during the winter, of the moral (sic) condition of the Army of Northern Virginia, have been realized. The operations which occurred while the troops were in the entrenchments in front of Richmond and Petersburg were not marked by the boldness and decision which formerly characterized them…

“From what I have seen and learned, I believe an army cannot be organized or supported in Virginia, and as far as I know the condition of affairs, the country east of the Mississippi is morally and physically unable to maintain the contest unaided with any hope of ultimate success.

“A partisan war may be continued, and hostilities protracted, causing individual suffering and the devastation of the country, but I see no prospect by that means of achieving a separate independence. It is for Your Excellency to decide, should you agree with me in opinion, what is proper to be done. To save useless effusion of blood, I would recommend measures be taken for suspension of hostilities and the restoration of peace.”

Davis and his cabinet assembled for a meeting at the Bank of North Carolina on the 22nd. By that time, Johnston had forwarded to them Sherman’s peace proposal. Davis asked each minister to provide a written opinion on the matter and share with the group the next day.

In Washington, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton notified Major General John A. Dix that Davis was trying to escape to Mexico with a “very large” amount of gold and silver. He urged Dix to use whatever resources possible to capture Davis before he could leave the country. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles directed Rear Admiral Samuel P. Lee, commanding the Mississippi River Naval Squadron, to be on high alert for a potential crossing by Davis and his party.

Meanwhile, Hampton wrote to Davis, “My only object in seeing you was to assure you that many of my officers and men agree with me in thinking that nothing can be as disastrous to us as a peace founded on the restoration of the Union… My plan is to collect all the men who will stick to their colors, and to get to Texas…”

The cabinet reassembled on the 23rd and unanimously urged Davis to accept the terms offered in the Johnston-Sherman agreement. As Attorney General George Davis explained, “Taken as a whole the convention amounts to this: that the states of the Confederacy shall re-enter the (U.S.) upon the same footing on which they stood before seceding from it.”

Davis was reluctant, but the clauses pertaining to upholding the rights of southern states and citizens appealed to him. He therefore accepted the terms, but if the Federal authorities rejected them, Davis expected Johnston to renew hostilities against Sherman. Davis wrote to Johnston:

“The Secretary of War has delivered to me the copy you handed to him of the basis of an agreement between yourself and General Sherman. Your action is approved. You will so inform General Sherman; and, if the like authority be given by the Government of the United States to complete the arrangement, you will proceed on the basis adopted.

“Further instructions will be given after the details of the negotiation and the methods of executing the terms of agreement when notified by you of the readiness on the part of the General commanding United States forces to proceed with the arrangement.”

All that Davis and his remaining government could do now was continue fleeing southward. He wrote to his wife Varina, who was traveling with their children as part of Lieutenant Parker’s naval escort currently at Washington, Georgia:

“The dispersion of Lee’s army and the surrender of the remnant which remained with him destroyed the hopes I entertained when we parted… Panic has seized the country… The issue is one which it is very painful for me to meet. On one hand is the long night of oppression which will follow the return of our people to the ‘Union’; on the other the suffering of women and children, and courage among the few brave patriots who would still oppose the invader, and who unless the people would rise en masse to sustain them, would struggle but to die in vain.”

Davis hoped for Varina and the children to travel safely “from Mobile for a foreign port or to cross the (Mississippi) River and proceed to Texas, as the one or the other may be more practicable.” Unbeknownst to him, Mobile was now in Federal hands.

He speculated on what the Federals might do with him if captured: “… it may be that our Enemy will prefer to banish me, it may be that a devoted band of Cavalry will cling to me and that I can force my way across the Mississippi. And if nothing can be done there which it will be proper to do, then I can go to Mexico and have the world from which to choose a location.”

Davis concluded, “My love is all I have to offer, and that has the value of a thing long possessed, and sure not to be lost.”

—-

References

Catton, Bruce. Grant Takes Command (Open Road Media. Kindle Edition, 2015), p. 471; CivilWarDailyGazette.com; Davis, Jefferson, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government: All Volumes (Heraklion Press, Kindle Edition 2013, 1889), Loc 21938, 22870-78, 22949, 22958-64; Denney, Robert E., The Civil War Years: A Day-by-Day Chronicle (New York: Gramercy Books, 1992 [1998 edition]), p. 559-62; Foote, Shelby, The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 3: Red River to Appomattox (Vintage Civil War Library, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Kindle Edition, 2011), Loc 20808-18, 21016-26, 21120-40; Fredriksen, John C., Civil War Almanac (New York: Checkmark Books, 2007), p. 585-86; Long, E.B. with Long, Barbara, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971), p. 677-81; White, Howard Ray, Bloodstains, An Epic History of the Politics that Produced and Sustained the American Civil War and the Political Reconstruction that Followed (Southernbooks, Kindle Edition, 2012), Q265

3 comments